Send any comments to the maintainer Roger Caffin

Outdoor activities carry their own risks of injury and death. Neither the Confederation nor the maintainer nor any other contributors to the FAQ pages have any control over what the reader does, and cannot accept any liability for any loss or accidents which the reader might suffer. The contents of this web site must NOT be relied upon for technical advice. Failing all else, read the NSW Civil Liability Act 2002. If you don't know what you are doing, get competent advice from your doctor.

A long contribution from David Jones has already been included here.

Tom Brennan's canyoning website has some wonderful canyon pictures, and good advice too.

More contributions, big or small, are invited.

It is a strange occupation which involves abseiling down narrow slots in the ground in darkness into freezing cold water, sometimes even abseiling under waterfalls, also freezing cold of course, swimming in narrow bottomless pools of freezing water in dark slots, getting almost nowhere in distance for a hard day's work, and then climbing up a steep hill with a pack full of wet gear. For some reason, all this seems quite popular.

The flip side is that the terrain you are going through is some of the most spectacular, on a very mini-scale, that I have ever seen. It can be surrealistically beautiful - although a long time-exposure may be needed to actually see it! The technical difficulties of real canyons makes walking at any standard seem incredibly simple by comparison, and there is a distinct satisfaction in traveling safely through this environment.

The sport as we know it is really only played around Sydney as nowhere else in the world has this sort of special sandstone rock. There is a belt of "canyon country" running up the west edge of the Blue Mts and Wollemi NP. There are a few other abseil areas such as the head of the Kanangra River and a couple of other rivers around Kanangra Walls, but (as far as the author knows, corrections invited) that's it for Australia. However, this canyon area is the finest in the world. Other countries have abseils down waterfalls (like at Kanangra) and cascading down rivers (France), but our sandstone canyons are very special. They are also quite dangerous, and beginners are strongly advised to go with experienced canyoners while they learn.

River cascading is practiced in France, with commercial groups much in evidence. We were crossing a small torrent at the entrance to a village in the Pyrenees and looked down at the rather wild (and flooded) creek in the limestone gorge below us. There were two signs on trees on the bank which reduced us to tears of mirth. One, by a lovely small beach at the end of a white water stretch, said "Exit is forbidden here". Apparently you had to exit on the other side. The other, which was quite large, said "Stop screaming here: you are entering the village". It gives you some idea of the commercial groups (and their age bracket) which play this game.

You are going to have to forgive a serious emphasis on hazards and safety precautions in this FAQ. We have seen too many accidents and rescues. It is easy enough handling ropes and abseiling in broad daylight; it's a different matter when you are floating in water under a waterfall with nothing to stand on and in the dark. Others can inspire you over the wonders of our canyons - and they are wonderful.

Almost by definition, canyon country is generally pagoda country on the west edge of the Blue Mts around Sydney. The sandstone rock that makes the pagodas is linked to the special sandstone which can be sculpted by the water into slots. As such, it is some of the trickiest country to get through I have ever seen. It is quite possible to get lost in a distance of 50 metres by going around the wrong side of a minaret, and then not be able to retrace one's steps. The terrain can be maze-like to a bewildering degree. It is also beautiful, and surprisingly fragile.

Some of the very well known canyons have tracks (of varying quality) going to them and back out, but even there one can easily get confused. More remote canyons, especially those not open to the commercial groups, may have no tracks, or sometimes may have deceptive wonbat tracks!

Once you are down into the canyon zone, it is wet. With water comes moss, algae, fungus, lichen, mud - all slippery. Any fallen timber starts to decay even as it topples over, and it develops a fine layer of slippery algae or fungus on the surface. Rocks are sometimes clean, but sometimes one rock out of two adjacent ones will have as much friction as a block of (melting) ice. The potential for slipping and spraining or breaking something is high. In fact, some popular areas used by commercial groups and youth clubs seem to have a helicopter rescue each weekend in the peak period. On one summer Sunday there were so many helicopters in mid-air over the Wollangambee River that we were genuinely concerned about being hit by colliding helicopters.

Regardless of the footwear wars waged elsewhere, this is one environment where boots are an unacceptable hazard. They do not grip on the greasy surfaces, and they are far too clumsy. In addition, they have an huge risk of jamming between boulders, usually under waterfalls. People have died and nearly died this way. The only recommended footwear for a canyon is a pair of Dunlop Volleys, They will not guarantee you won't slip, but that strange grooved pattern and soft rubber are your best chance of staying upright. In case you are wondering how serious this really is, take note that many bushwalking clubs will not permit people to go on club canyon trips unless they are wearing Volleys. This is not a religeous argument: this is a safety issue.

The figure of eight descender is the cheapest around, and so is fairly popular. Unfortunately it is also very dangerous in a canyon where the bottom of the rope is not hanging free. The problem is the way the rope twists around the descender: it twists the rope badly and you end up with a bundle of kinks and tangles. If you get one of these jammed in your descender while you are half way down you are in big trouble. It is equally possible to run into the problem at the bottom, when you take your weight off the rope. Just as you do so, the twists tangle around the descender and you find you can't get enough slack to disconnect from the rope. If you are floating in the water under a waterfall when this happens, you can be in trouble again.

One way of handling this is to always carry several prussik loops in your pocket or on the back of your harness (out of the way!), and to know how to use them. They can let you can take your weight off the descender while you sort out the mess. You need to have practiced using prussik loops beforehand of course.

This problem is so severe that many clubs do not permit the use of figure of eight descenders on club trips. They prefer the use of "in-line" descenders, where the rope is not twist around. The various "racks" are strongly recommended instead, like the one to the right.

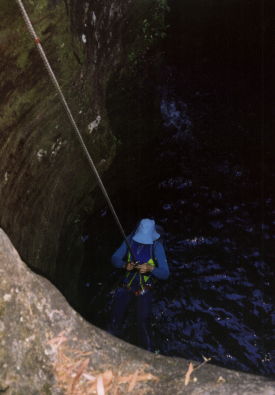

Your danger here is pretty obvious: you may have little idea of what you are doing. Sometimes it is worth waiting a while for your eyes to adapt to the darkness, but in some places there isn't even enough light for this to work. Experience, caution and a headlight are recommended. When the darkness is combined with the ropes tangling and you are trying to swim with a pack on, you have the potential for a real mess. The only significant light in the photo to the left was from the flash: the rest was largely done by touch.

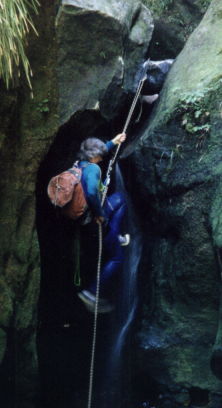

There are several dangers here. The first is a bit like darkness: you can't see what you are doing. The second is the slipperiness of the rock: always a problem when there is a lot of water around. The third is far more serious and is specifically due to the amount of water pouring down over your head: if you get into any difficulties, you may find yourself running out of air. This induces panic, which doesn't help. Rescue from here is extremely difficult, especially as there may be little time to organise and the person in trouble may have the only rope. It is crucial to be wearing a strong hat or helmet with a brim when abseiling down a waterfall: it diverts the water from your face and lets you breath. It is also very important to recognise when you are entering sucha situation and to plan what you are going to do, so you can keep going even if you can't see.

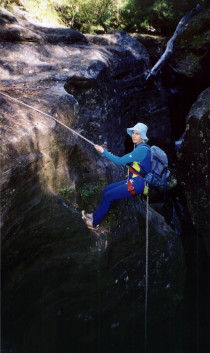

Many abseils start off on an undercut ledge. You end up swinging under the ledge as you go over. Done properly it looks easy, but it requires some skill. What sometimes happens is that your rack gets caught against the rock as you go over the last bit of the lip and you swing underneath. The way the rope is tight against the rock makes it extremely difficult to do anything, even putting a prussik loop on the rope. The other common happening is that your fingers around the rope get caught. To be sure, you can pull your fingers clear, but you are going to leave a lot of skin on the rock. You may find it hard to hold the rope after this: another accident in the making.

Three things help here: keep your rack very close to your waist rather than up near your face, keep your upper hand off the rope for a moment (scary at first), and do the last bit over the edge dynamically, with a little jump and drop. Of course, this may mean you swing under the overhang blind: this too can be dangerous. The first person down has to be very careful, but at least can then advise the rest.

A bit obvious of course - but what are you going to do? When a knot jams in a crack of rock, pulling harder is extremely unlikely to help. On the other hand, dare you rely on the knot staying jammed long enough for you to climb back up the rope to free it? The best strategy is for the first person down (and the second last person as well) to check that the ropes will slide easily.

Getting things caught in the descender can leave you hanging in space, which has its own problems. Bits of clothing are the obvious dangers: loose shirts especially. However, long hair can be extraordinarily painful, fingers can get caught, and we have even seen one poor girl catch a very intimate part of her upper anatomy in a descender. The message for all of these is to lean away from the rope! Train yourself to NOT clutch the rope closely to yourself: instinctive, but dangerous. Competant instruction in abseil technique is very valuable.

This one is less well known. When you are stuck on an abseil, your weight is hanging inside your harness. Only too often a simple waist harness can constrict your chest. Harnesses with leg supports are better, but cut off the circulation in your legs, and this can be equally dangerous after a little longer. This can lead to breathing difficulties, and seems to have been responsible for several deaths. In one case a novice became stuck in the dark and eventually died. A more experienced person abseiled down to help and also became stuck - and also died. Both are believed to have asphyxiated. Not all abseils are down simple open faces, so you have to watch your footing and not slip into a jam.

There is nothing quite like getting part way down an abseil to find that the old anchor you used has broken and is coming down with you. Of course, often the slings you find are fairly new and are probably OK. Sometime they will look rather old, and you are faced with the difficult decision of whether to leave one of your own "very expensive" slings behind. We suggest that the cost of a sling is not high compared with your life. Of course, this requires that you be carrying some spare slings or tape with you. Just in case. Failing that, you may need a change of underwear.

If you decide the sling(s) you found are not reliable, consider removing them when you replace them with a new one. That way the place does not get cluttered up. Make very sure of course that what you leave behind is better than what you remove. After all, it's your life you are safeguarding first and foremost.

We ourselves have seen a water in a canyon go from ankle deep to more than two metres deep after rain. Can you imagine how fast the water was going as well? That's something a lot of people fail to fully appreciate beforehand: the force the water can exert on your body at a waterfall or rapid is truly frightening. Yes, we have made this mistake ourselves, and we ended up quite scared. Actually, we nearly ended up dead. Getting out of the river was a pretty hair-raising exercise; getting out of that section of the canyon withoiut going back in the water was equally 'interesting' But two metres is not a lot of rise: the photo to the left looks innocent, but that's a log jammed across the canyon above the canyoner's head. There's only one way it got there: in a flood. The message is, if it is raining, don't go into the canyon, or look for ways to get out urgently.

Commercial parties love to have their clients jump into all the pools. I guess it adds to the thrill, but I also suspect they encourage it because it is faster than abseiling. Having explored the snags and rocks at the bottom of many pools out of curiosity, I have to say I would always abseil carefully rather than jump. I may be a wimp, but I am a live wimp. (Overtones of disapproval? Yes.) Unless, of course, I could jump onto a Lilo. That's always satisfying, provided you stay on top. Makes a huge and satisfying splash too.

Sprain or break an ankle while walking and it isn't too hard to find a comfortable and safe spot and wait to be rescued. In some cases you can even make it out yourself. This doesn't work in a canyon. There, you have to be able to indulge in what we call "extreme 4WD walking": using both feet, often at strange angles and in strange sequences, and both arms, also in peculiar ways. ANY impairment of mobility will bring you to a complete halt - usually in a cold dark wet environment. Hypothermia coming up very quickly.

The most common rescue technique these days is a helicopter. Fly over, locate patient, drop down and either land adjacent or winch up. Easy. Now try that in a canyon like the one to the left. The walls are maybe a few metres apart and the bottom is 20 metres down. The rock walls are twisted, and there may not even be a direct line to the sky. The valley above is steep-sided and the trees are maybe 30 metres tall, and close together.

Well, maybe the resuers could carry you some way out on a stretcher? Oh yeah? When it is all you can do to get yourself through using both legs and both arms - and you slipped anyhow and had an accident?

We have placed some emphasis on safety and rescue here because this sport is so hazardous and rescue is so difficult. That much said, experienced players do go canyonning regularly and safely - but they are using a huge store of knowledge and skill to do so. Do not expect to learn all this in one or two supervised trips.

Well then, what is the best way of learning? There are several ways, not all equally good, but which seem to be common enough.

to be completed

Clubs, commercial outfits, group sizes

Ropes and descenders

Skills

Wet suits

Footwear

Lilos, flippers

Food

Toilet

© Roger Caffin 1/6/2002